Replacing the High-rise

This is about the adverse impacts of high-rises and a proposed alternative for them in San Francisco, a city that always encouraged new architectural ideas. Out of respect for the scale and spirit of its older neighborhoods, the city now faces a housing crisis, which it tried to solve with high-rise buildings, whose large carbon footprints are major contributors to climate change. While the city continues to pollute the environment with steel and concrete skyscrapers, it overlooks its history of sustainable neighborhoods and a building technology that could provide San Francisco with the necessary places for people to live pleasantly, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and preserve the city’s scale.

This first of a four-part article looks at changes in the city’s built landscape over the past sixty years and how we got to where we are today.

High-rises in Candlestick?

July 26, 2018 “Item 4, 2016-100378, 1600 Jackson St: Proposed to continue until September 27, 2018.”

The old man sat down in one of the back rows of Room 400 at San Francisco’s City Hall only to hear the clerk tell the seven members of the Planning Commission that the permit application for 1600 Jackson would be put off for at least two months. 1600 Jackson was the old man’s excuse for being there, because the building was what he looked at when he stopped for coffee most mornings at the Bell Tower. Granted, the little one-story restaurant sporting a mini-bell-tower atop a Spanish tile roof wasn’t any Starbucks, but its setback from Jackson Street provided a spot for half a dozen tables where old men like him could sit in the sun and think about what San Francisco used to look like.

He was doing just that as he remained in Room 400, admiring the Manchurian oak-paneled dais where the planning commissioners sat. One of them named Richards, addressing a woman that apparently shared the old man’s worries about high-rises, said, “I think it will be helpful to look at the plan for the Shipyard and Candlestick Point. The development proposes low rise and high-rise buildings. The Candlestick Point has buildings over 30 stories.” The old man didn’t like to think about more high-rises. This Richards was talking about 30 stories. That may have made sense to Richards, but not to him.

Years ago, he would have stood up and been heard, but the spoken word didn’t come easily and he didn’t want to make a fool of himself by stammering his way through disjointed thoughts he’d been tossing around for years. Especially in front of this tough group of city planners.

I was once one of them.

The first high-rise since 1927

When I moved to San Francisco in 1956, the most recently built high-rise was the 32-story Russ Building, completed in 1927. Nothing like it had been built since, so I had little to go on when, working for Anshen & Allen Architects, I was asked to evaluate property at the corner of Kearney and California streets for a possible new office building. I analyzed construction figures and found that foundation and elevator costs increased as you went up, but so did rental income. Also, the more floors, the more occupants, and the more elevator shafts for cabs to carry them up. At some point the shafts would eat up all the floor area and I had to find a reasonable cutoff, the point where rents would still cover the accumulated costs. My evaluation of all the factors determined that the optimum height for an office building for that property would be thirty-five stories. I put the methodology and conclusion in a report that was set aside as we considered what the building might look like for the client, Mr. Ralph Davies.

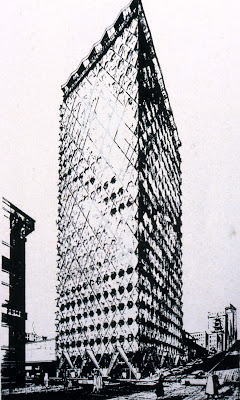

A high-rise in San Francisco would be different. This wouldn’t be masonry-clad like the Russ Building, but something more like the revolutionary Lever House completed just five years before in New York, whose steel frame was covered with a glass curtain wall. A San Francisco high-rise would be different, because of the earthquake forces that pushed horizontally and had to be carried down to the foundations where they were dispersed. Design techniques for this had been evolving over time; but never implimented on a skyscraper. There was, however, an office building around ten stories tall under construction near the Davies’ site. We met with two engineers responsible for its structural design, and they described how earthquake forces were picked up in diagonal braces at different points and as many diagonal beams as possible were needed to shift the horizontal loads to the columns that carried them to the ground. Reacting, I asked, “Could all the loads be carried down with diagonal beams or braces and the vertical columns be eliminated?” The engineers agreed and I sketched a pattern that looked like a giant trellis. Using this, we developed an exterior elevation that, from a distance, looked like a large quilt, with octagonal windows set between the diagonal bracing.

We felt this “unique” design could echo Mr. Davies’ entrepreneurial spirit. He’d created the second largest oil company in the Middle East, owned a gold mining corporation, and recently acquired the American President Lines. On the day we presented the conceptual drawings, Davies walked up the stairs to the conference room of the old Dollar Building, nodded to the group, walked around the room, and briefly looked at each drawing, before wordlessly disappearing back down the stairs. His aid reported that Mr. Davies only asked about the windows: “Were they sort of round, like portholes?” “Yes, sir.” “We have enough of those on the ships!”

Anshen & Allen later produced a different award-winning solution for the site. As for the thirty-five story optimum building height, Davies decreed that nothing over twenty-one stories should be built that far from Market and Montgomery Streets. Within three years, his International Building was flanked by Hartford’s thirty-four stories right across California Street and, in 1969, Bank of America’s fifty-five stories on Kearney Street. For me, the experience designing a high rise building was challenging but was still just conceiving a square meter of skin and applying it to a box. My diagonal structure concept lay fallow until SOM designed Alcoa’s San Francisco Headquarters near the Embarcadero Center. Since then, it has appeared in major cities throughout the world.

San Francisco’s special places

San Francisco’s high rise buildings were concentrated in the Financial District, which had gradually grown up close to the waterfront and its shipping. The intersection of Montgomery and Market Street was its titular center and home to the major banks, whose classical facades and elegant porticoes provided a singular sense of place that would disappear. Three blocks west,The Downtown District grew up around Union Square as merchants pulled their goods from the nearby docks to shops that soon matured into multi-story department and specialty stores. Union Square buildings, with full glass show windows linked together, provided a different panorama from Montgomery Street, yet a similar sense of embracing those that walked by.

The rest of the city’s forty-seven plus square miles were divided into established neighborhood. The one with our home for many years was near the 3200 Pacific Block. Although just another San Francisco block, it had its own sense of place. All the residences had differing architectural features, but they were tied together by similarly shingled walls with black window trim and black front doors that created a uniform corridor one passed through going down the street. Their Bay Area Shingle Style was probably inspired by similar work being done by East Coast architects who clad beach “cottages” for affluent clients with weathering cedar shingles; but it was made easy in San Francisco by the new lumber barons who had vast redwood, cedar, and fir forests to exploit in the coastal groves of Northern California.

The Pacific block provided a place where one felt in a special neighborhood. Another one was Jackson Square, a setting without any square that boasted a Barbary Coast without any coast. Many Jackson Square buildings survived the 1906 quake and were reconstituted as offices for professional people and designer showrooms. Most of the blocks between Battery and Columbus that were built in the 1880s had coats of paint sand-blasted away to reveal red brick walls that, like the shingled houses further out on Pacific, created a sense of community of common interests. It was the daytime home of lawyers, accountants, architects, and advertising agents, who were there not only because it was cheaper space than in the Financial Center but because it had an identity all its own.

This was the kind of place Jane Jacobs wrote about with, “While you are looking, you might as well also listen, linger, and think about what you see.” Walking along its sidewalks, as you stopped by the Knoll furniture showroom of the 1960s, you remembered it once had a stage featuring striptease artists. Over on Jackson Street an antique store was a former distillery, with an identifying plaque proclaiming, “If, as they say, God spanked the town for being over-frisky, why did he burn his churches down and spare Hotaling’s whiskey?”